If you combine all our current knowledge of statistics and astronomy, it's nearly comical to believe we're the only intelligent life in the universe. It's easy to get lost in the numbers thrown around - there are billions of stars and planets in our galaxy and billions of galaxies. Humans are rather bad at fully understanding such large numbers.

Despite where this article might lead, it isn't really about science - its about thinking big. Big enough to consider that if there are any aliens with the ability to come visit us, they would almost assuredly not care to.

Stephen Hawking, the famous physicist, said in an interview that

aliens visiting us would be similar to Christopher Columbus first landing on North America (not a good event for native Americans). His idea being that they would come for our resources, not with any particular purpose of friendship.

There are a few problems with that thought however. To introduce the idea, consider most any space movie in existence. Movies are of course, just movies, but they have shaped our thinking about meeting aliens. And small thinking it is indeed.

From what movies tell us, it would seem that scientists from alien races pretty much focused on 3 primary technologies: faster-than-light travel, energy weapons, and artificial gravity. Movies don't highlight artificial gravity much because given our limited view, we pretty much expect gravity to just work and shooting a movie without it would be an unnecessary pain. So, screw it, all movie alien races invented artificial gravity.

There's a lot of implied technology thereafter (i.e. movie aliens don't often get sick and seem to not worry about eating) but that's not the fun stuff to think about. Lasers, phasers, and pew-pew-energy-blasters however, are fun to think about.

Did you ever wonder though - why these same scientists who made these neato energy weapons never bothered to develop targeting systems? They still rely on crappy biological reflexes to aim them. It's even sillier when alien robot/cyborgs that can outperform humans in every other way somehow still aren't so great at aiming their phaser zapper. They miss just as much as the humans do, and by that I mean - a lot. Of course, Star Wars would have been a short film if every shot stormtroopers made hit Han Solo but it would have made more sense.

Its actually rather ridiculous when you think about it - we (as in current state of human tech) already have automated targeting systems that work well with our doofy bullet-guns. We literally have targeting systems in existence today better than anything you saw in Star Wars.

Truth is, given how far along we already are - by the time humans develop usable energy weapons - we'll have awesome targeting systems to match. We won't miss. It is with fantastically geeky sorrow that I proclaim that there'll never be an energy pistol or rifle I'll get to shoot. Sure, there'll be energy weapons. Sure, they'll shoot. But it won't be me "aiming" them. They'll darn well be perfectly happy aiming themselves. Chances are I'll probably just be running away.

Movies get to ignore whatever they wish. However, reality dictates that science tends to advance in all directions at the same time. Not only because there's some level of constant pressure in all directions, but because advances in one field often accelerate many others (much like the invention of the computer accelerated all other fields of human science).

If Stephen Hawking is right, then he is saying a race of aliens have, at a minimum, perfected faster-than-light travel (or be willing to travel for several thousands of years at sub-light), conquered longterm biological effects of space radiation, and mastered extreme long distance space navigation just to come to earth and steal our water.

Another consideration that I rather enjoy is that if aliens would come here for resources, then that inherently implies an economic model into their decision. By definition, they need and value resources. Consequently, coming here to get them must have been their most economical choice. Getting them somewhere closer to home or manufacturing them must be more "expensive" (in some sense of the word) than the cost of them traveling all the way here, gathering our resources (probably atomizing us in the process), and flying them home.

While not impossible, that seems like an unlikely set of events - both technologically and economically. Again, even we have (expensively) already mastered alchemy. We even have the tech to create matter from energy. Imagine that tech in a hundred years, or two hundred, or whenever it is you think we'll be able to travel several light years for a mining expedition. What would be cheaper and better, forge the plutonium at home or send a galactic warship with thousands or warriors (and miners) to some far off planet?

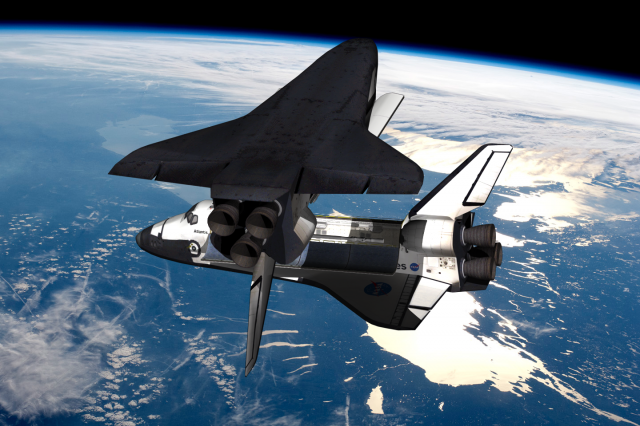

From where we are now, we're not even close to being able to get to Proxima Centauri (the closest star to us besides the sun) much less a place where we think there's a actual planet. Even the technology required even to get us to Proxima Centauri in less than, say, 1000 years would require tech orders of magnitude from what we have. Propulsion, sustainability, radiation protection, nanotech - you name it.

Comparatively (and no disrespect to NASA) our existing space program involves us putting bombs underneath rocket-ships, blowing them into space with enough air supply for a few weeks, and bringing them back before the astronauts lose too much bone mass and/or the Tang runs out. If getting humans to another star system is a 100 on some "technology ability scale", we're a 2 which is not comparatively far ahead of say, poodles - who are probably at a 1.

The idea that they might come to Earth to colonize hits a similar argument. You could argue that terraforming (or xenoforming for them I suppose) could be a technology more advanced than FTL travel. With that assumption, you could imagine an alien race within the technological sweet spot of knowing how to travel across the universe but not alter planets to suit their biological needs. Coming to colonize Earth (again while likely blasting us into being "no longer chemically active organic matter") could make sense. But this ignores the fact that several other requisite technologies would probably make their need to colonize obsolete.

Before they had FTL travel, they likely spent many decades traveling at less that light speed. Even if not, chances are their ships are quite hospitable to themselves. In fact probably more like sailing biodomes than ships - someplace they could live indefinitely. But a biodome is probably the wrong inference - assuming their bio-scientists were at work while their space-propulsion engineers were perfecting FTL, they would likely have quite minimal external environmental needs. Stuff like air and food has long been technologied away.

The only thing something like Earth could give them is a place to stand on. Xenoforming a planet might be out of their reach, but creating ships to live in is by definition, well within their reach. The home-iness of living on a planet probably is questionable. It won't be as hospitable as their own ships.

So why else might they want to come here? Maybe they want to trade with us. Well, yeah, right. If you've gotten this far it's obvious we have no tech that would interest them. Maybe we'd be able to trade them some local arts and crafts or pottery or something - but other than that, they won't be interested in our childish technology.

Well, maybe they want to study us? Well, maybe. It seems probable that if they were on a mission to study life forms, we would not be the first planet they would have visited. Chances are, they've seen other life forms already. Probably some at least similar to us. Statistically speaking, we might be interesting but not all that interesting.

Oh yeah - and statistically speaking - what about statistics? Remember, my thesis is that all fields of science tend to advance simultaneously. That includes math and statistics. In order to make FTL ships, pew-pew-lasers and artificial gravity you're going to need math (and computers) that are light years ahead of ours.

Let's say they could use their super-advanced Hubble telescope, and see our solar system (at some point in the past). They'd see earth in the goldilocks zone for life. They'd know its land and atmospheric composition. They'd see it's oceans and know the planet's temperature variations. They'd see Jupiter acting as a bodyguard soaking up dangerous asteroids.

Even today, if we saw such a solar system, we'd have a pretty good idea that life could be there. If our math, statistics and knowledge of other life forms was 1000 times more advanced, how accurately could we predict that the life forms there would have 2 nostrils? How close could we come to guessing exactly what those life forms would be like?

And if we couldn't get exact - how close would we care to? Does it really matter? In other words, with enough data and statistics (the foundation of what humans like to call "machine learning" or "artificial intelligence") they already know we're here. Just like we know there was water on Mars or high temperatures on Venus.

Even with that however, we're still thinking too small. It's not just their science and tech that's advanced - you need to expect that they have too.

Twenty years ago if I asked you how many feet were in a mile (and you didn't know) you could go to a library and look it up. Ten years ago, you could go to a computer and google it. Today, you can literally ask your phone.

It's not a stretch at all with the advent of wearable computing that coming soon - I can ask you that question and you'll instantly answer. The interesting part of that is that I won't know if you knew the answer or not - and more importantly, it won't matter. If information is reliably fed directly to you from an external source, there'll be no advantage to remembering anything.

How many years before we have a brain interface to Google? You'd know everything. And its not crazy to think that soon after we'd find ourselves limited by how slow our brains process information. The obvious next step being to augment our brains, our thinking, and in the process - augment who we are. That's what our scientists will be working on then (and of course, are actually already working on).

How would you change if you had instant brain-level access to all information. How would you change if you were twice as smart as you are now. How about ten times as smart? (Don't answer, truth is, you're not smart enough to know).

Now, let's leap ahead and think about what that looks like in 100 years. Or 1000. Or whenever it is you'll think we'd have the technology to travel to another solar system. We'd be a scant remnant of what a human looks like today. Movies like to show aliens with over-sized heads and that may well be the case, but not because of biological evolution. Technological evolution will have long surpassed the snail-pass of biological evolution by then (read most any Ray Kurzweil book to hear this a lot).

The question of why aliens might "want to come here" is probably fundamentally flawed because we are forming that question from our current (tiny) viewpoint. The word "want" might not apply at all to someone 1000 times smarter than us.

If we discovered a fish-like creature on Europa today it would be fascinating for us to study it. If however, we were 1000 times smarter and had spent the last 1000 years finding fish-like creatures across the galaxy, and could with 99.99% accuracy predict the exact existence of such creatures from light-years away, it probably wouldn't be all that interesting to go study another one.

The bottom line is that if an alien race is capable of getting here, all the other technology they've requisitely developed in the meantime would make the trip unnecessary at best - and more than likely, simply meaningless.

We're just not as advanced or as important as we like to think. In the end, there's no compelling reason to think they'd be interested in meeting us - we simply think too small.

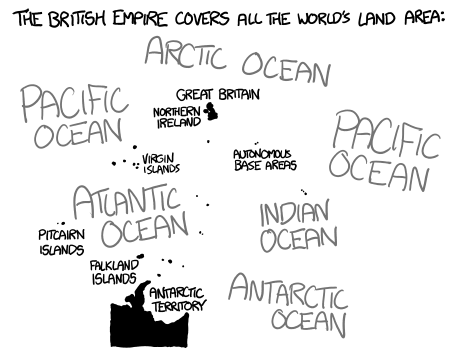

![The walls of Buckingham Palace are lined with [in case of emergency, break glass] boxes. Inside each one is a cup of tea.](http://what-if.xkcd.com/imgs/a/48/empire_eclipse.png)

Brb, making our own one. Share on Facebook.Share on Twitter.Share on Google+

Brb, making our own one. Share on Facebook.Share on Twitter.Share on Google+